Exhibitions

Exhibition history

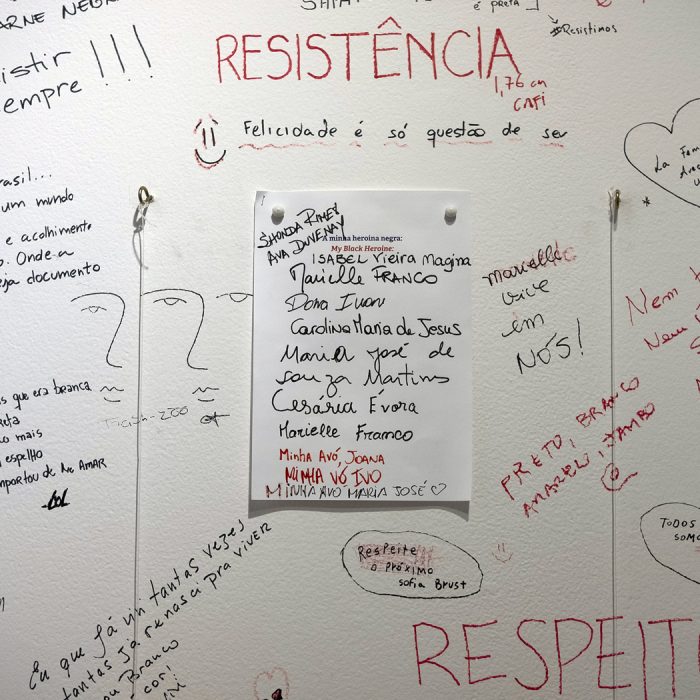

Mãe Preta (Black Mother) began in 2015 with an invitation to create a new piece for a group show in a gallery located in Rio de Janeiro’s colonial centre. On the gallery’s door, we found a fragment of a print by travelling painter J. M. Rugendas called Negresses of Rio de Janeiro (1835), which portrays a Black woman carrying her baby using an African wrap-cloth. At this time, the debate around feminism in Brazil was beginning to gain prominence the public sphere, and in light of new archaeological evidence found during urban regeneration in preparation for the 2016 Olympics, the city of Rio confronted its own past as the largest slave port in the world. The uncovering of major landmarks related to slavery brought forth a renewed interest in the memories and legacies of our slave past, which had been buried beneath successive layers of urban modernisation. These findings have provided channels to access memories of great value to Black populations, even though there is still a long way to go before more substantial reparations are made.

Within the ‘Black field’ – a term coined by historian Flávio dos Santos Gomes to define the field of complex social and race relations in the history of the enslaved population in Brazil –Rugendas’ image became the trigger to investigate the fragile relationship between the representation of motherhood within the memory of slavery in Brazilian visual history and the struggle of Black women and mothers in Brazilian society.

In 2016, Mãe Preta became an exhibition project following an invitation to exhibit in the memorial site of what is known as the largest slave cemetery in the Americas, the Pretos Novos Cemetery, in Rio de Janeiro. Today, the memorial for the archaeological site includes Instituto de Pesquisa e Memória Pretos Novos – a research center for Afro-Brazilian studies – and Galeria Pretos Novos de Arte Contemporânea – a contemporary art gallery. It is estimated that thirty thousand bodies of African captives, many of them children, are buried there. These were enslaved people who did not survive the Transatlantic crossing and whose bodies were deposited only inches from the ground. The site is located only a few hundred metres from Valongo Wharf, one of the main places of landing and trading of African slaves in the continent.

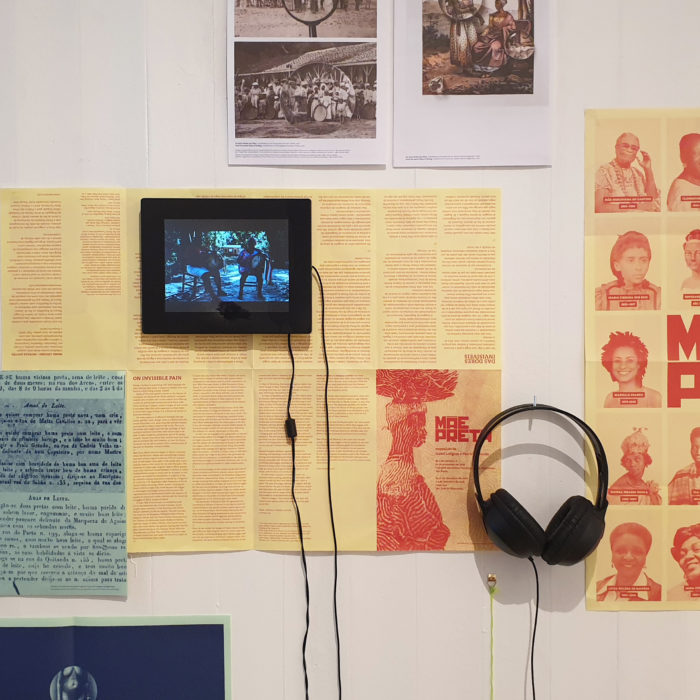

In each new city where Mãe Preta is shown, we look for new points of inflection in the local context to uncover new aspects in the relationship between motherhood and slavery.

In 2017, Mãe Preta was shown in Belo Horizonte with additions taken from the context of Minas Gerais and its importance in the gold mining colonial economy. Here, we dove into classified ads for wet nurses in local newspapers during the 19th century, equating the demand for black milk to the demand and greed for gold that characterizes the Brazilian gold rush from the late 18th to the late 19th centuries.

In 2018, we examined the history of the Mãe Preta monument located in downtown São Paulo, which is a major landmark for the memory of slavery in the city centre. This city square is currently undergoing a period of urban degeneration along with the slow yet forceful erasure of significant Black memories from the urban space. This square has also become a dystopic scenario where dozens of homeless people huddle around the statue, following the collapse of the Wilton Paes building in May 2018, which made the acute housing crisis in the continent’s richest city all the more apparent. The statue forms a link to the monument Zumbi dos Palmares – which pays homage to one of the earliest Black heroes in Brazilian history, a maroon who held up a resistance against the Portuguese for several decades in the 17th century – located in the nearby Praça Antônio Prado, as a poor attempt to re-inscribe the Black memories that the urban planning has torn asunder.

Also in 2018, this time in São Luís do Maranhão, in northern Brazil, we engaged with quilombola, or maroon communities – originally communities of runaway slaves in the time of slavery, and which have persisted as a form of communalistic organization within certain Black communities ever since – where the struggle for Black memory is strongly connected to the struggle for land and the respect for diverse ways of living in the Amazon region, which is continuously being threatened by large-scale mining and logging companies. Maranhão’s encantaria – rooted in an unique array of Afro-Brazilian social and religious practices that permeate all forms of local resistance – is embodied in the centuries-old knowledge of ‘enchanted’ midwives, who are responsible for both physical and spiritual healing in these communities.

In 2021, a new iteration of the exhibition was made in Campinas, in northern São Paulo state, a region with rich farmland for coffee plantations and one of the last bastions to fully eradicate slavery, despite abolition in 1888. The profitable coffee economy made landowners continue the conditions of slave labor into the early 20th century, at the same time as masses of poor European laborers migrated to Brazil to substitute slave labor. Because of this, the memory of slavery in Campinas has suffered a process of historical effacement, which is today being reclaimed by the sizeable Afro-Brazilian population in the city. One of the forces fighting for historical reparations is the Casa de Cultura Fazenda Roseira and Comunidade Dito Jongo Ribeiro who in the past decade has created an important Black cultural and political movement to reclaim ancestral Afro-Brazilian cultural traditions in the region. As a collaborator in the project Fazenda Roseira has creted a series of cyanotypes of ritual and medicinal plants – an ancestral herbarium – cultivated in the old plantation house that houses the cultural institution, and shares that knowledge with exhibition visitors.

Unknown to global audiences, Campinas also plays an important role in the invention of photography in the early 19th century. It was in this city, then known as Vila de São Carlos, that the French draftsman and inventor Hercule Florence (Nice, 1804- Campinas, 1879) settled after having served in the Langsdorff expedition whose goal was to map and document the fauna, flora, peoples and customs of Brazil. Working alongside a local apothecary, Florence invented one of the first ways of fixating images with light, and allegedly invented the term “photography” – writing with light. Florence’s application for a patent for his invention from the hinterlands of Brazil and arrived only too late in cosmopolitan Paris, moments after Daguerre had already patented his invention. Florence made numerous inventions during his long lifetime, but his work fell into obscurity until a foundation was set up by his descendants in the late 20th century. Since then, there is an annual photography festival in his honor, or which Mãe Preta is one of the participants in the 2021 edition. The use of syanotypes reminds of Florence’s early experiments and is a way of connecting two strands of forgotten histories – that of slavery and that of the dawn of photography, into one gesture.